Singing Nose | 오퍼센트 2021

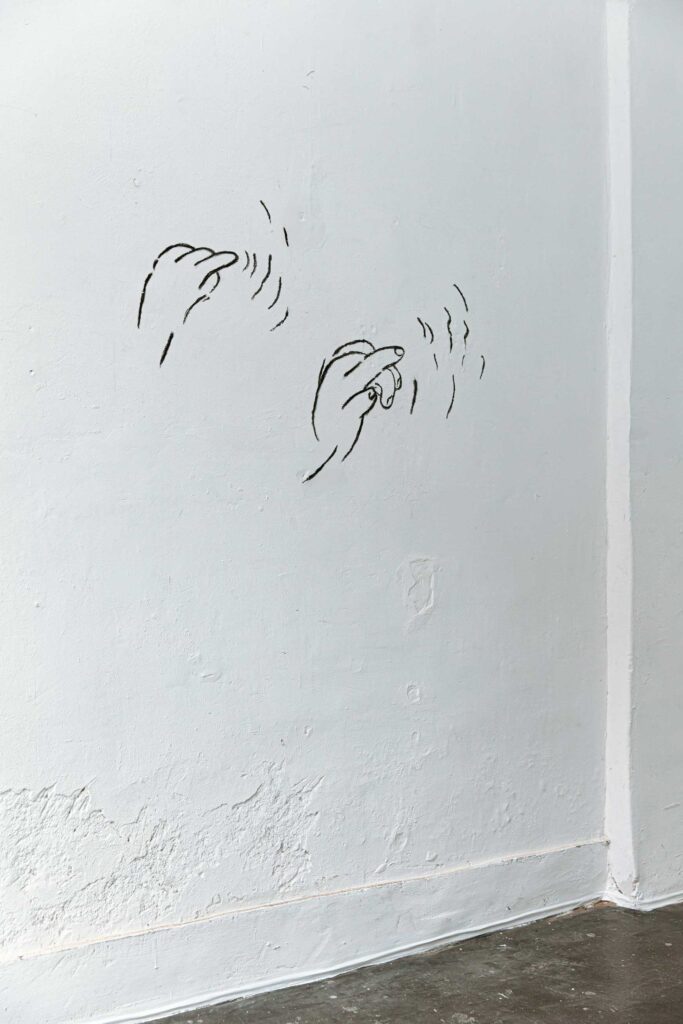

싱잉 노즈, 2021, 벽에 목탄, 7채널 오디오 설치 가변크기

Singing Nose, 2021, charcoal on wall, seven-channel audio, installation view

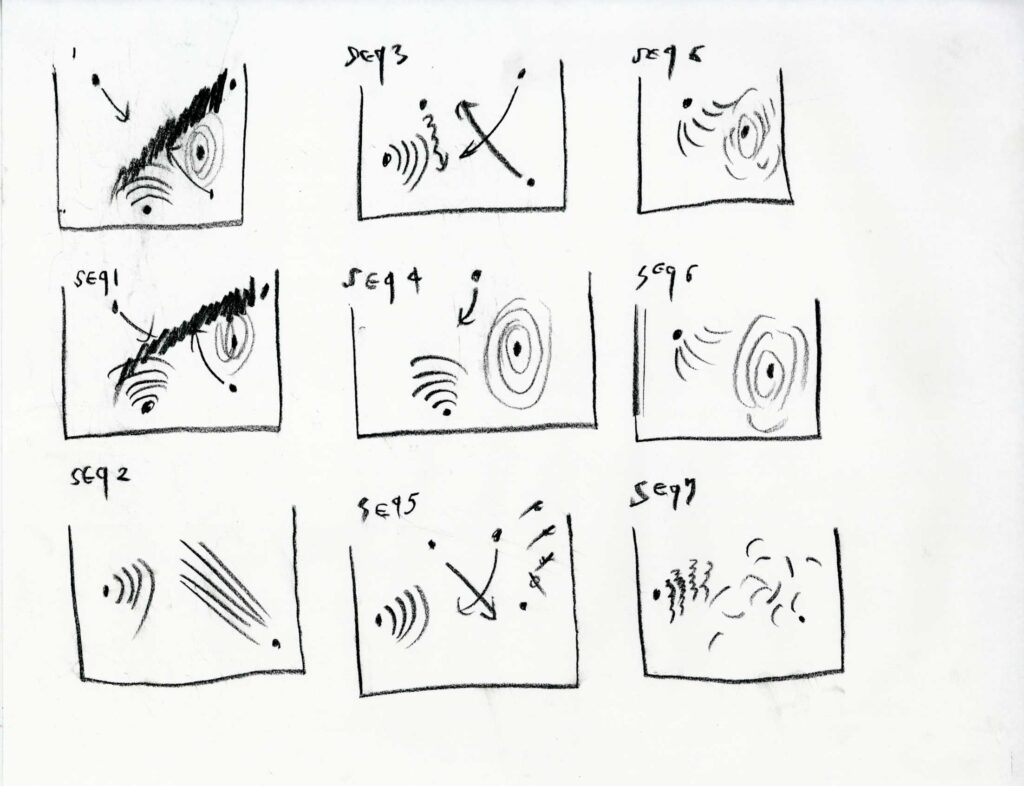

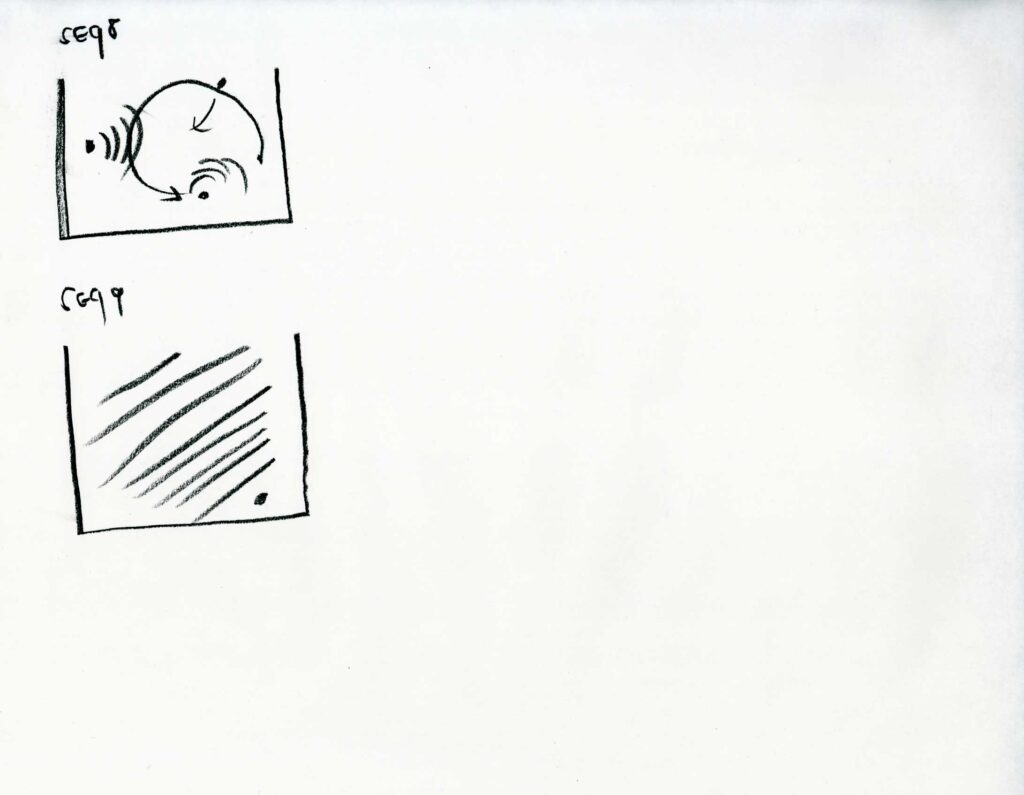

sound sequence 9 drawing

2020년 코로나19 팬데믹 이후 김지영(109)은 다른 이들의 콧노래를 모으기 시작했다. 물물교환이나 대가를 지불하는 방식으로 서울 시민 40여 명의 콧노래를 수집했다. 그것들은 지난 겨울 퍼포먼스 《콧-노래 산책》에서 작은 깃발이 되었다. 콧노래를 시각 이미지로 만든 자수 드로잉이 박힌 깃발에 사운드 장치를 달아 콧노래가 나오게 했다. 관객들은 그 깃발을 하나씩 들고 눈 덮인 북한산을 걸었다. 깃발에서 나오는 콧노래에 귀를 기울이거나, 그것을 따라해 보거나, 상관없이 자기의 콧노래를 부르거나 하면서 움직였다. 타인의 콧노래와 함께 이동하는 경험이 중요했던 《콧-노래 산책》과는 다르게, 전시 《싱잉노즈》에서는 고정된 장소에서 좀 더 많은 이들의 개별 콧노래와 관람객이 느끼는 다양한 감각에 집중한다.

김지영(109)은 소리를 보여주거나 만지게 하는 것에 대해 말한다. “소리라는 것이 공기를 만지는 것 같은, 촉각적인 것이라는 생각이 들어요. 또 콧노래의 모양, 콧노래들끼리 만나는 순간을 시각적으로 그려보는 것이 재미가 있었고요.” 그는 소리를 내고-듣는 행위에, 진동을 만들고-(촉각적으로)느끼는 행위와, 시각 이미지를 그리고-보는 행위를 교차시킨다. 그는 콧노래가 가지는 특수성에 대해 잘 알고 있는 것처럼 보인다. 나에게서 나와, 나를 향하는 노래. 그러나 다문 입 속에서 내는 그 소리는 온전히 귀를 향하고 있는 것이 아니다. 그것은 노래이지만 청각만으로는 느껴지지 않는다. 입 안에서 만들어지는 동시에 스스로를 울리는 진동, 귀가 아닌 피부와 근육으로 느껴지는 어떤 간질간질함이 있다. 내가 만든 소리가 나를 몸 안에서 어루만지는 것 같은 기분. 어떤 감각의 발신과 수신 사이에 거리가 아주 좁혀져 ‘나의 몸’ 혹은 ‘내 몸의 어느 기관 하나’가 되어버릴 때, 어떤 감각은 다른 감각과 경계가 흐릿해지기도 한다. 예를 들어 코의 경우, 소리라는 감각은 들어서 아는 것이 아닌 피부로 느껴서 아는 것이 되기도 한다. 작가는 그것을 콧노래가 가진 ‘누군가 어깨를 두드려 위로하는 것 같은’ 느낌이라고 말한다.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Kim Ji-yeong (a.k.a. 109) has collected the sounds of other people’s humming. She has compiled the humming of about forty people through barter or by paying them in proportion to the length of their contribution. In last winter’s performance A Humming Walk, that humming was transformed into small flags. She created embroidered flags that visualized humming into images, attached to which were sound devices that played the humming sound. Participants walked the snow-covered trails of Bukhansan Mountain, holding the flags. As they walked, they variously listened to the humming emitted by the flags, hummed along with it, or just hummed something completely unrelated to the sound. Unlike A Humming Walk, in which the experience of moving while carrying the sound of others’ humming was paramount, the exhibition Singing Nose concentrates on the individual humming of more people and on the diverse sensations felt by the visitors within a fixed space.

Kim Ji-yeong (109) discusses the process of rendering sound visible or tangible: “It occurred to me that sound was something tactile, like touching the air. I also had fun visually imagining the form of humming, or the moments that one strand of humming met another.” She interweaves the act of making sound with that of listening to sound; that of creating vibrations with feeling vibrations (in a tactile manner); and that of drawing images with viewing images. It would appear that she has a solid understanding of the particularity of humming—a song that emerges from oneself even as it is directed towards oneself. However, sound produced within a closed mouth is not necessarily directed toward the ears. It is a song but is not limited only to the auditory senses. A sound produced inside one’s mouth that is simultaneously a vibration of oneself possesses a sort of tickling sensation felt not by way of the ears, but through skin and muscle. It feels as though the sound that I have made is soothing myself from within. When the distance between the transmission and reception of some senses is minimized to the point that those senses become part of “my body” or “an organ of my body,” those senses blur the boundaries of other senses. For instance, the nose thus creates sensations of sound that can not only be heard but also felt through the skin. The artist posits this as humming possessing the sense of “consoling oneself as if someone was patting me on the shoulder.”